11th July, 1926: thirty-two drivers line up on the grid at AVUS, Berlin, to take the start of the inaugural Grand Prix of Germany. Among them is a young Rhinelander by the name of Rudolf Caracciola, a mechanical engineering student and car salesman attempting to launch a racing career.

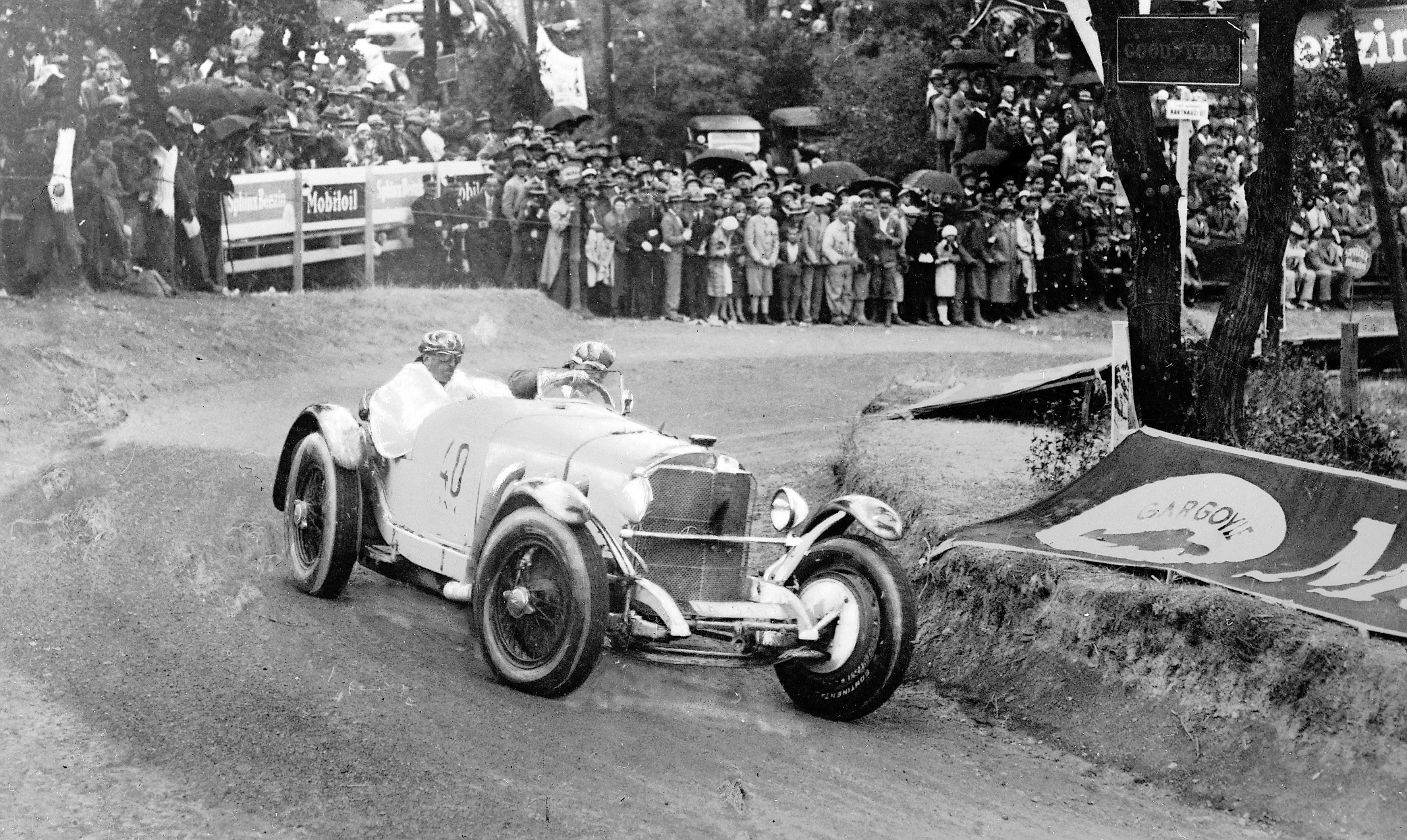

Fielded as an independent entry in a loaned and outdated Mercedes-Benz M218, Caracciola’s first Grand Prix start was almost a disaster when he stalled his engine off the line and eventually got going several minutes behind the field. But when heavy rain washed the AVUS track shortly after, Caracciola was given a second chance; as the more seasoned drivers ahead of him careened off the road, Caracciola pressed on, unaware of his position but determined to finish, and after twenty laps he emerged astonished from the dense fog and rain to find himself as the winner of the first-ever German Grand Prix. The press hailed him as the Regenmeister, or “Rainmaster”, and a winning partnership between Caracciola and Mercedes-Benz was born.

Rudolf Caracciola’s performance at the 1926 German Grand Prix was a prime example of the racing legend he was well on his way to becoming—one who would be remembered for his supreme ability and resolve in even the most challenging circumstances, and for the integral part he played in the pre-war successes of the Silver Arrows.

Caracciola was born in 1901 in Remagen, Germany, and like most early Grand Prix drivers came from a background of wealth and class: his ancestors were of the historic House of Caracciola, a prominent family in the Naples aristocracy whose members included princes, politicians, artists and clerics. Aided by such an upbringing, it wasn’t long before the young Rhinelander had developed a fierce passion for motoring, and by the age of fourteen—despite pressure from his father to attend university—he was already set on a future as a professional racing driver.

His first opportunity to realise that dream came when he took up an apprenticeship at the Fafnir factory in Aachen, and he found success as early as his first races for the company in finishing fourth at AVUS and first at the Opelbahn in 1922. But it was in the following year, after a brawl with an occupying Belgian soldier forced Caracciola to relocate to Dresden, that the German really began to make his mark on the European motoring world: finding new work as a Daimler salesman, Caracciola was allowed to enter up-to-date Mercedes touring cars in prestigious events across Germany, and went on to take numerous rally and hillclimb wins before his infamous German Grand Prix victory in 1926.

From then on, Caracciola’s star continued to ascend. Using the prize money from his first Grand Prix win, he married his girlfriend Charlotte and opened up a Mercedes-Benz dealership of his own in Berlin—all the while continuing to race state-of-the-art Mercedes’ tourers across Europe, in races such as Le Mans, the Mille Miglia, and the first Grand Prix of Monaco in 1929. He secured his second and third German Grand Prix wins at the Nürburgring in 1928 and ’31 (the latter requiring those same wet weather skills that took him to victory at AVUS in ’26) and also displayed his prodigious talents outside of circuit racing with two European Hillclimb titles in 1930 and ’31 and overall victory in the 1931 Mille Miglia.

In 1932 Caracciola was forced to move to Alfa Romeo, after the Wall Street Crash and resulting global economic depression drove Mercedes to withdraw from motorsport altogether. Alfa Romeo was easily one of the most respected teams of the era and, as the dominant force in Grand Prix racing that year, enabled Caracciola to score podiums in Monaco, Italy and France, as well as a fourth win in Germany and a third consecutive hillclimb title.

But although the partnership was a fruitful one, it was far from harmonious. Alfa Romeo would initially only offer Caracciola a contract as an independent entrant, as the marque doubted his capacity to adapt from his old Mercedes-Benz tourers to their lighter Italian cars; even when he was promoted to the works team, his finishes behind Italian teammates Tazio Nuvolari and Baconin Borzacchini were plagued by accusations of team favouritism. Compared with his close, respectful relationship with Mercedes-Benz racing manager Alfred Neubauer, Caracciola’s time at Alfa Romeo was undeniably one of intense strain, and proved to be just the beginning of a period of great personal trial for the German.

Just a year after joining Alfa Romeo, Caracciola found himself without a seat once again when the Italian marque followed Mercedes in pulling its factory squad from competition. His response was to join forces with friend and fellow racer Louis Chiron and set up Scuderia C.C., a privateer entry built around three blue-and-white Alfa Romeo 8Cs and a Daimler-Benz truck to transport them—but at the first race of the year in Monaco, Caracciola’s brakes failed in practice and he was sent hurtling into the wall at Tabac, suffering an impact that destroyed his car and left the German with a badly fractured right thigh.

After doctors at the local hospital doubted he would ever race again, Caracciola was determined to defy them and spent the rest of the year recovering in private in Italy and Switzerland. But even as his leg began to heal, he was hit by an even greater tragedy when his wife was killed in an avalanche whilst skiing in the Swiss Alps; under the pain of his injuries and his grief, Caracciola retired in mourning from public life and all but abandoned his racing career.

That may well have proved the end of Rudolf Caracciola’s story, had it not been for the efforts of his one-time teammate Louis Chiron. During their years as racing rivals, the Monegasque had developed a close bond with Caracciola and continued to visit him through his isolation, and it was during one of those visits that Chiron persuaded Caracciola to drive the lap of honour before the 1934 Monaco Grand Prix—and despite still suffering considerable pain in his right leg, the experience of returning to a Grand Prix circuit was enough to ignite Caracciola’s flame for racing once again.

As if by design, Caracciola’s return to the track coincided with the revival of the Mercedes-Benz racing team, which in 1934 was making its way back to the top of Grand Prix racing as the global economy recovered. In April of that year Caracciola had his first taste of the new Mercedes challenger, the supercharged W25, in an AVUS test session; and even in the face of numerous setbacks (chiefly mechanical issues with the W25 and a right leg that, once healed, was now two inches shorter than the left) the Rainmaster proved that he had lost none of his skill in his brief retirement, finishing second at the Spanish Grand Prix and first in the Klausenpass hillclimb before the end of the season.

The following year, Caracciola made a triumphant return to the top of the rostrum when he won in sweltering heat in Tripoli, his first Grand Prix victory since 1932. This marked the beginning of Mercedes-Benz dominance in the European Championship, and over the course of 1935 Caracciola took his W25 to further wins in France, Belgium, Switzerland and Spain as well as collecting a third place in Germany—with the trauma of his Monaco crash clearly behind him, Rudolf Caracciola was firmly back where he belonged and was all but unchallenged in becoming the 1935 European Drivers’ Champion.

The Rainmaster began his title defence in characteristic style in 1936 by winning the torrential opening round in Monaco, but over the duration of the season the W25 proved second-best to the new Auto Union Type C, and Caracciola lost the title by some margin to countryman Bernd Rosemeyer. Their championship battle sparked an intense rivalry between the two Germans both on and off the track, one which saw a flashpoint at the 1936 Swiss Grand Prix when the stewards ordered Caracciola to cede position to Rosemeyer in punishment for being too aggressive in his defence of the lead.

For 1937, spurred on by their loss to Auto Union the previous year, Mercedes-Benz introduced the brand-new W125. With an eight-cylinder, 5.6-litre engine capable of producing over 600 BHP, the W125 was considered the most powerful race car ever built—and with Grand Prix engine capacity limited to just 3,000cc the following year, that became a title it would hold until the introduction of turbo-charged engines to Formula One in the 1980s.

Emboldened by the might of his new Mercedes-Benz challenger, Caracciola put the frustration of 1936 behind him in convincing fashion, winning three of the ’37 season’s five championship Grands Prix to reclaim his European title. He followed up his racing success by taking a streamlined W125 to the Frankfurt–Darmstadt Autobahn, and taking aim at the previous road speed records set by Auto Union’s Hans Stuck and Rosemeyer—to this date, the average speed of 432.7 km/h (269.9 mph) set by Caracciola over a flying kilometre remains the fastest ever speed recorded on a public road.

Mercedes-Benz then continued its Grand Prix dominance in 1938 with the W154, a new design built to match the reduced 3.0-litre engine formula. Caracciola opened the season with second place in a Mercedes 1-2-3 in France, and took another two podiums and victory in Switzerland—again in the wet—to secure his third and final European Drivers’ title, sealing his legacy as the most successful driver in the championship’s history; Mercedes-Benz also finished the season with each of its drivers occupying the top four positions in the final standings.

Despite the great heights achieved by both parties that season, 1938 turned out to be the final chapter of Caracciola’s and Mercedes-Benz’ Grand Prix success story. The 1939 championship was abandoned after the outbreak of war in September, and with Hermann Paul Müller leading a fightback for Auto Union, Caracciola could only manage one final career win—fittingly that was a sixth German Grand Prix win at the Nürburgring, making him the last German to win a home Grand Prix until Michael Schumacher in 1995, and still the most successful driver in that event’s history.

During the Second World War, Caracciola and his new wife Alice lived in exile in Lugano, Switzerland, during which time the injuries to his right leg returned to pain him. In 1946 he was invited to take part in the Indianapolis 500 in a loaned Thorne Engineering Special, but was struck on the head by a bird during practice and crashed into the south wall, leaving him with severe concussion and in a coma for several days. He returned to active racing six years later when Mercedes-Benz invited him back to drive a 300SL in the 1952 Mille Miglia, in which he finished fourth despite being given an inferior engine to his teammates Hermann Lang and Karl Kling; but in that same year, a heavy accident at the Grand Prix of Berne resulted in a fractured left leg and forced him into retirement for good. In 1959, after enduring a variety of serious illnesses, Caracciola suffered a fatal liver failure and died at the age of 58.

Though his story may not be as widely known as those of later Formula One legends, there is no doubt that Rudolf Caracciola is a name that deserves to be remembered. He was a driver of unparalleled skill, possessing the same calculated resolve as Niki Lauda or Fernando Alonso, the formidable versatility of Graham Hill, and with a flair for wet weather driving to rival the great Ayrton Senna; moreover, his legacy includes speed records and a tally of six German Grand Prix wins that still have yet to be surpassed nearly eighty years on.

In the words of his Mercedes manager Alfred Neubauer, Rudolf Caracciola was “the greatest driver of the twenties and thirties, perhaps even of all time. He combined, to an extraordinary extent, determination with concentration, physical strength with intelligence. Caracciola was second to none in his ability to triumph over shortcomings.”

Deputy Editor

Where did you get your info from?