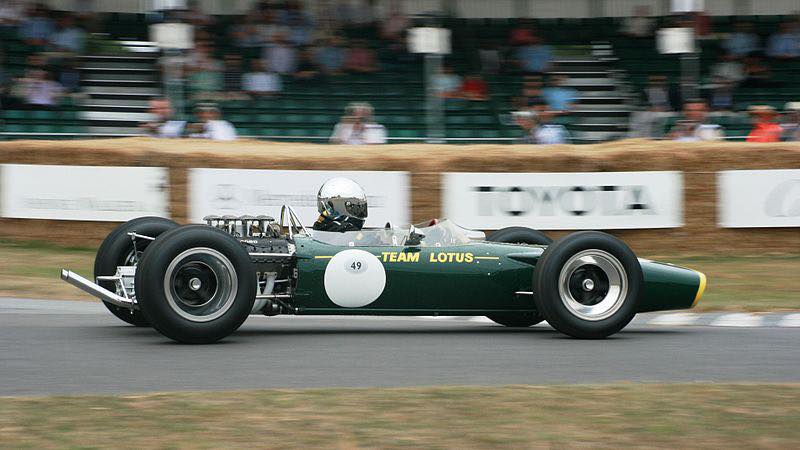

If you were asked, what’s the most successful car in Formula One history, what would you say? Likely enough, 1988’s all-conquering McLaren MP4/4 (or, if record wins in a season is your metric, Mercedes’ W07). The most beautiful? Jordan’s 191, drizzled in the sexiest of liveries thanks to 7UP. But what about the most important? Well, that accolade falls to none other than Lotus’ not-so-difficult second album- the 49.

The 49 began life as Colin Chapman’s newest lovechild back in 1967, built to replace the ageing 25 that had escorted the wondrous Jim Clark to two World Championship titles. The 25 was a revolutionary car in its own right, being the first to have a fully stressed monocoque chassis (this made it 3x stiffer and much stronger than the chasing field), but the 49 would be an even smarter beast. It would go on to, unknowingly, shape the course of Formula One itself.

The first reason for my claim can be found in Formula One’s, and possibly all of racing’s, most iconic powerplant: the Ford-built, Cosworth-engineered Double Four Valve, otherwise known as, you guessed it, the DFV. This engine was a colossus, placing Cosworth on the map as an established go-to for private teams and even title hopefuls, and lasted 19 seasons, right up to Martin Brundle’s foray in the 1985 Austrian Grand Prix. And it started its journey nestled in the back of the 49.

The first thing to know about the 49’s usage of the DFV is that Team Lotus built the car around it. Not metaphorically, literally. The engine was a genuine stress-bearing member of the car, bolted between the monocoque and suspension/gearbox. Stiffness, already a major string to the 25’s bow? That was boosted, and with the issue of anti-vibration mounts now a non-factor, the 49 was lighter for it. Effectively all Formula One cars followed this technique, the first ever-present standard the 49 introduced to open-wheel racing’s elite series.

The DFV was a driving force behind Lotus’ successes for the next 16 seasons, with every World Championship won by the Team Lotus outfit after its introduction powered by Cosworth’s masterstroke. When the 49 debuted, back in 1967, they had a monopoly on DFV usage- they were to be the only team putting it to use. While they didn’t manage to win the ’67 title, with unreliability plaguing Jim Clark’s efforts, the 49 did join an established list of greats, Clark taking its maiden win at the first attempt in Zandvoort, and Cosworth’s unanticipated decision to put the DFV on the open market for teams to buy didn’t dent Lotus’ success.

1968 would see Graham Hill take up the mantle of team leader with aplomb, after the tragic death of Clark in a Formula Two race earlier in the year, and he delivered the last of his two titles. And it’s here where we touch on the second sport-changing innovation the 49 delivered, this time one which has been not just an ever-present, but a snowballing force in open-wheel racing: front and rear wings.

In Monaco, Chapman and his team were rattling their heads for ways to lather downforce on their machine, and the solution came from Can-Am racing: Chaparral had been using front splitters and rear wings on their racing cars to generate downforce, and slice through the air. Thus, Team Lotus debuted a similar take, with aerofoil wings bolted directly to the front nose and rear suspension. And they worked to perfection, with Hill winning the race in dominant fashion.

Other teams would take time to adopt, but ever since the 49 gave way to wings, they would never leave the sport. By the early 70s, everyone had to adapt or perish, and a modern-day Formula One car simply can’t be driven without a front and rear wing in place (see Michael Schumacher’s struggles without one, for instance). The wings tacked onto the 49 evolved over time, too: the front section remained largely the same, but the rear spoiler morphed from a rising engine cover, to a full three-slotted wing, to a towering Goliath of a spoiler scraping the clouds above.

So let’s recap: the 49 not only acted as carrier for the sport’s most synonymous, and widely appreciated engines, it also introduced two critical aspects of Formula One design to the sport, both of which are still integral to the cars we have today and very likely the future ahead. It also bears the success it deserves, with two Drivers’ and Constructors’ Championship titles in ’68 and ’70, and also outside of itself shaped history, with Jochen Rindt being the only Formula One driver to ever posthumously win a world title.

The MP4/4 may have created new standards itself, what with the beautiful lowline chassis layout, the MP4/1 before it brought carbon fibre into the mix, and Renault’s RS01 from 1977 lays claim to turbocharged engines, but for sheer breadth of innovation, not one car has had such a shaping effect on the sport than the 49.